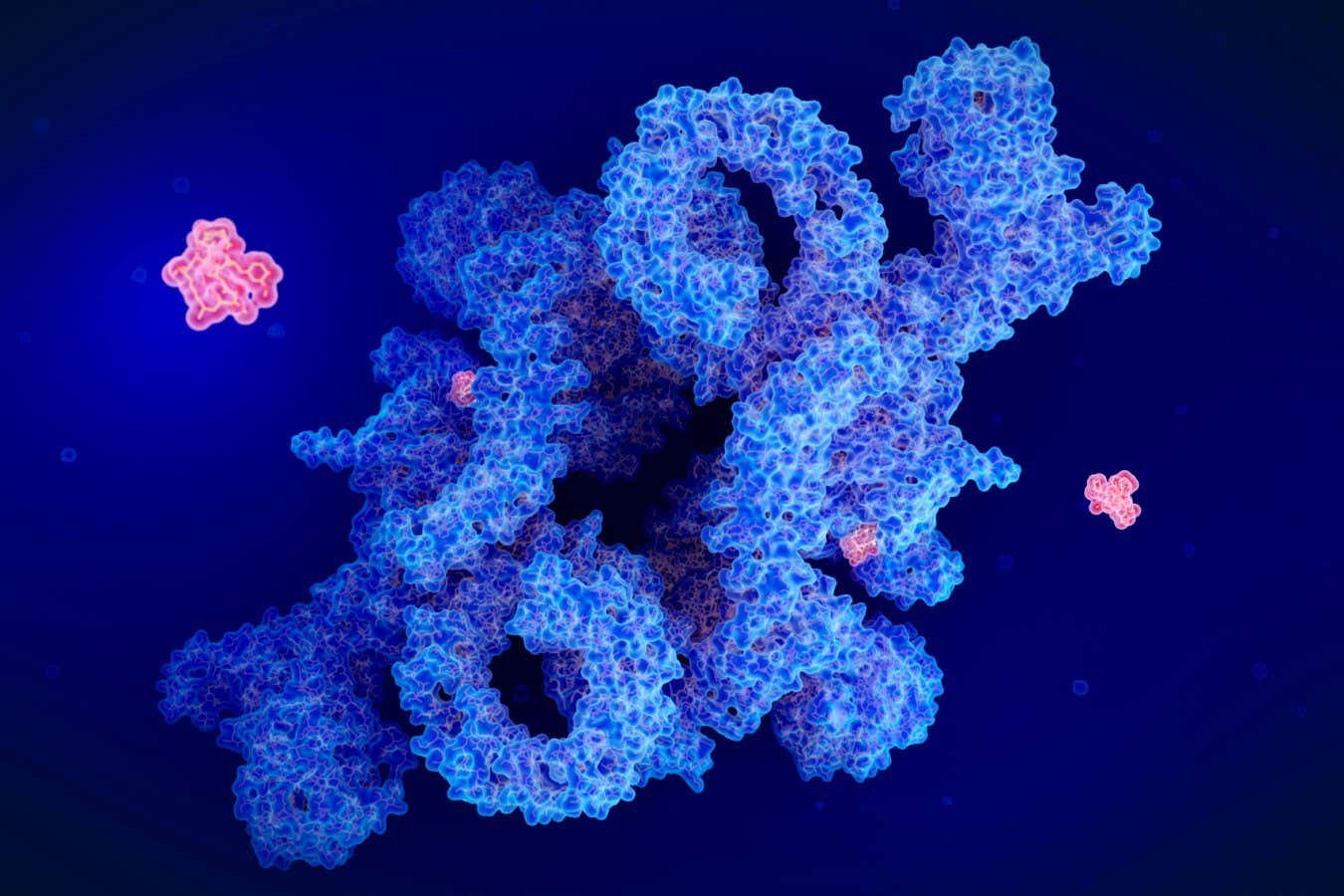

Illustration of the drug rapamycin (red) that blocks a protein called mtor (blue)

Science Photo Library/Alamy

The drug Rapamycin’s anti-altar effects could at least partly be to prevent DNA damage in our immune cells-a understanding that can help us free its potential as a life extension.

Rapamycin, originally developed as an immune suppressive means of people undergoing organ transplantation, blocks the effect of the MTOR protein, which is the key in cell growth and division. At low doses, it has been shown to have a life life in animals such as flies and microphone, possibly by interfering in process that leads to signs of age, such as inflammation, cellular degradation and reduced fun for the mitochondria that drives our cells.

Now Lynne Cox at the University of Oxford and her colleagues has found that Rapamycin also seems to stop DNA damage in a type of immune cell. DNA damage is an important driving force for the aging of our immune system that speeds up aging throughout the body.

The researchers revealed this when they treated human immune cells called T cells, a type of white blood cells fighting infections, with rapamycin, while also exhibiting for an antibiotic called zeocin causing DNA damage.

They found that rapamycin reduced DNA damage and tripled the survival rate of cells compared to those who were only exposed to Zeocin.

The researchers saw no evidence that this occurred as a result of another of the effects of rapamycin, such as stopping cellular degradation. “Whether you use Rapamycin before causing damage, during the injury or after the injury, we always see this mechanistic effect,” said team member Ghada Alsaleh, also at the University of Oxford.

The speed of the effect also suggests that it happened directly. “The impact is such that it seems that it affects DNA damage responsibility and the accumulation of [DNA] Lesions within 4 hours, so I don’t think it can be a downstream consequence of the other thing affected, ”says Cox.

Matt Kaeberlein at the University of Washington in Seattle says the study supports Rapamycin, which has a direct protective effect on DNA but “stops shortly after a final mechanism”. The researchers hope to find this by examining rapamycin-induced changes to RNA and proteins produced in immune cells.

In another part of the study, the nine men aged 50 and 80 awarded to take either 1 milligrams per year. Day rapamycin or a placebo. After eight weeks, blood tests showed that the T cells for the men on Rapamycin had less DNA damage. There was also no decrease in the total number of white blood cells in the EITH group, suggesting that rapamycin does not adversely affect the immune function. “We have shown that it is not harmful in low doses, and this is a critical point,” says Cox.

Tackling DNA damage to immune systems can be a route towards reducing overall aging, says Cox. And Alsaleh says rapamycin could even be used preventively, perhaps to avert DNA damage to the astronauts exhibition for cosmic radiation.

“Rapamycin could also be particularly useful for aspects of aging where DNA damage is a primary driver, such as skin aging,” says Kaeberlein, pointing to evidence that topical rapamycin reduces markers for aging in man

Zahida Sultanova at the University of East Anglia, UK, notes that the placebo control experiment was only performed on older men, it is also important to carry out trials in women and people of different ages. Studies in non-human animals suggest that rapamycin may have gender spaces and age security effects.

Topics: