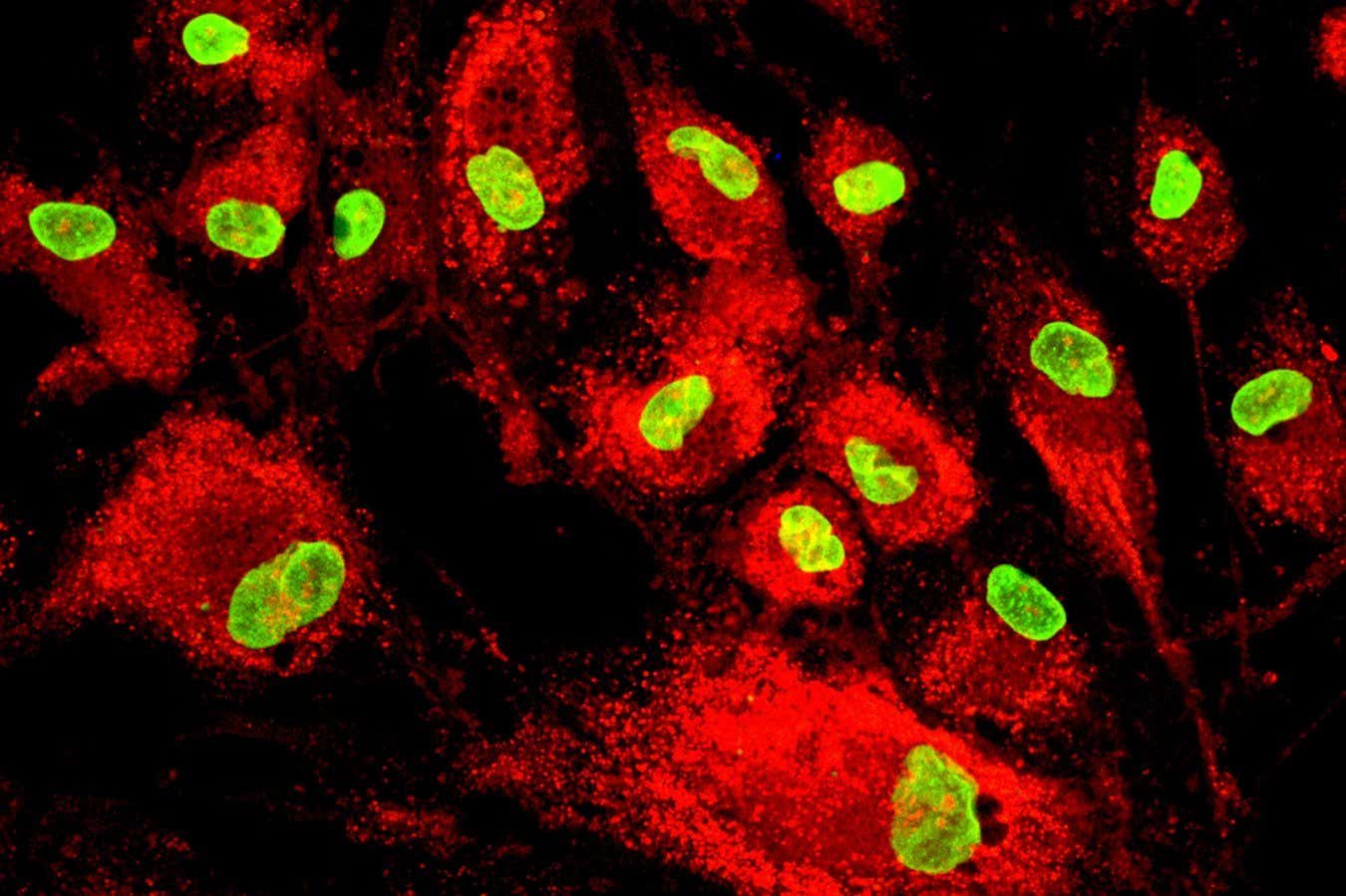

Mesenchymal stem cells labeled with fluorescent molecules

Vshivkova/Shutterstock

People who received an infusion of stem cells shortly after a heart attack were less likely to develop heart failure than those treated with standard care, according to the largest of these trials to date. The finding provides some of the strongest evidence yet that stem cells can help the heart repair itself.

After a heart attack, the heart muscle is permanently damaged and weakened, often leading to heart failure – when the organ cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s demands. Currently, there is no treatment other than a transplant or heart pump that can restore heart function.

As a potential solution, researchers have turned to stem cells, which have the unique ability to transform into other cell types. But previous studies examining their use after a heart attack have shown mixed results. For example, a 2020 trial involving 375 people found that cells derived from bone marrow, including stem cells that develop into blood cells, did not lower the risk of death more than standard treatment, such as cardiac rehabilitation programs and drugs to lower blood pressure, reduce blood clots or lower cholesterol.

Armin Attar at Shiraz University in Iran and his colleagues took a different approach: they used mesenchymal stem cells, which can differentiate into structural cells such as cartilage and fat. These stem cells also release molecules that reduce inflammation and spur surrounding tissue to regenerate.

The team collected mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood and infused them into the hearts of 136 people within three to seven days of their first heart attack. While these stem cells could be taken from the participants’ own fat and bone tissue, it can take a month to grow enough of them for an infusion, Attar says. Using them from umbilical cord blood allowed the team to administer the treatment much more quickly, potentially amplifying the effects, he says. A separate group of 260 people received standard care after their first heart attack.

Three years later, those who underwent stem cell therapy were, on average, 57 percent less likely to develop heart failure and 78 percent less likely to be hospitalized for the condition than those who received standard treatment. They also saw significant improvements in the heart’s ability to pump blood, suggesting that the treatment helps heart tissue regenerate after damage.

“This is a big step forward,” says Attar. Although the therapy did not reduce the risk of death during the study period, the fact that it lowered hospital admissions is still remarkable, says Hina Chaudhry of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. “Heart failure is the leading cause of hospitalization in the United States,” she says.

But 80 percent of the participants were men, making it less clear how the therapy affects women, who are more susceptible to heart failure after a heart attack, Chaudhry says. However, Attar and his team did not find that the results differed by gender in a separate analysis. The study was also limited to younger adults; all participants were between 18 and 65 years old. “It would be good to see a breakdown of age groups because younger patients just have a more natural regenerative ability and they recover better from heart damage,” says Chaudhry.

These findings are the strongest indication yet that stem cells can help restore heart function after a heart attack. But the treatment does not cure the heart completely. “There is no drug, no therapy on this planet that replaces what is lost [heart muscle cells]. And that’s what’s really going to be a game changer in the field,” says Chaudhry. Still, “all this research is teaching us more about the regenerative process in the heart and how to get there,” she says.

Subjects: