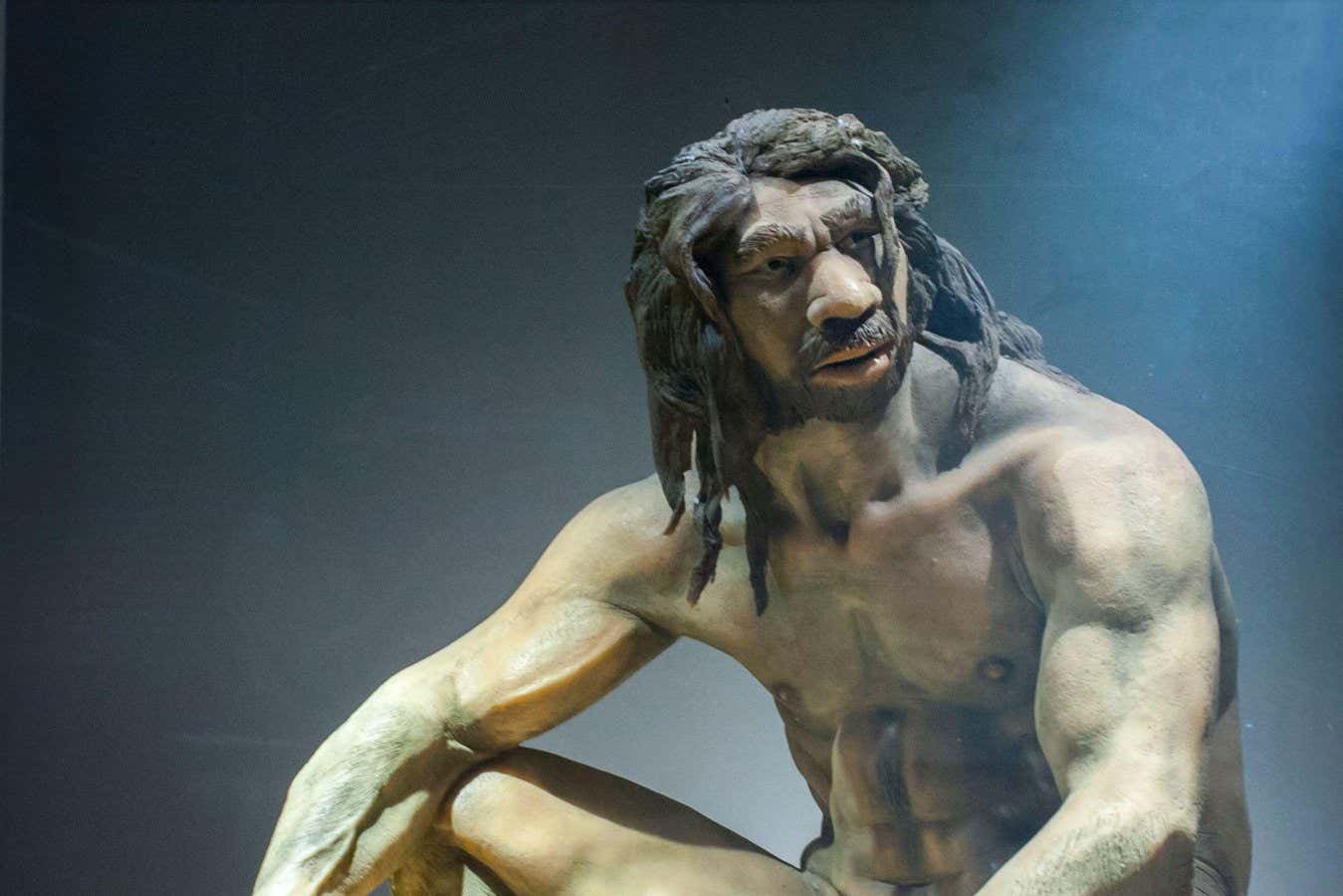

A model of Homo Heidelbergensis, which may have been the direct ancestor of Homo sapiens

WHPICS / ALAMY

A timeline for genetic changes in millions of years of human development shows that variants associated with higher intelligence appeared fastest about 500,000 years ago and were closely followed by mutations that made us more prone to mental illness.

The results suggest a “compromise” in brain development between intelligence and psychiatric problems, says Ilan Libedinsky at the Center for Neurogenomics and Cognitive Research in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

“Mutations related to psychiatric disorders apparently involve part of the genome that also involves intelligence. So there is an overlap there,” says Libedinsky. “[The advances in cognition] Maybe come to the price of making our brains more vulnerable to mental disorders. “

People split from our closest living relatives – chimpanzees and bonobos – more than 5 million years ago, and our brains have tripled in size since then, with the fastest growth in the last 2 million years.

While fossils allow researchers to study such changes in brain size and form, they cannot reveal much about what these brains were able to do.

Recently, however, genome-wide association studies have examined many people’s DNA to determine which mutations are correlated with features such as intelligence, brain size, height and different kinds of diseases. Meanwhile, other teams have analyzed specific aspects of mutations that suggest their age, giving estimates of when these variants first appeared.

Libedinsky and his colleagues brought both methods together for the first time to create an evolutionary timeline for human brainsal genetics.

“We do not have any traces of the cognition of our ancestors in terms of their behavior and their mental problems – you cannot find them in the paleontological items,” he says. “We wanted to see if we could build some kind of” time machine “with our genome to find out.”

The team examined the evolutionary origin of 33,000 genetic variants found in modern humans that have been linked to a wide range of features, including brain structure and various goals for cognition and psychiatric conditions, as well as physical and health -related features such as eye form and cancer. Most of these genetic mutations show only weak associations with a trait, says Libedinsky. “The links can be useful starting point, but they are far from deterministic.”

They found that most of these genetic variants emerged between 3 million and 4000 years ago, with an explosion of new ones in the last 60,000 years – around the time Homo sapiens made a greater migration out of Africa.

Variants associated with more advanced cognitive abilities developed relatively recently compared to them for other features, says Libedinsky. For example, those related to fluid information-in-the essential logical problem solving appeared in new situations-for about 500,000 years ago on average. It is about 90,000 years later than variants associated with cancer, and almost 300,000 years after those associated with metabolic functions and disorders. These intelligence -bound variants were closely followed by variants associated with psychiatric problems about 475,000 years ago on average.

This trend was repeated from about 300,000 years ago, when many of the variants that affect the shape of the cortex brain’s outer layer, which was responsible for cognition with higher order-ducked up. In the last 50,000 years, several variants associated with language developed, and these were closely followed by variants associated with alcohol dependence and depression.

“Mutations related to the very basic structure of the nervous system come a little before the mutations of cognition or intelligence, which makes sense, since you first have to develop your brain to get to higher intelligence,” says Libedinsky. “And then comes the mutation of intelligence before psychiatric disorders, which also makes sense. First, you need to be intelligent and have language before you can have dysfunctions on these capabilities.”

The dates also match the evidence that suggests that Homo sapiens acquired some of the variants associated with alcohol consumption and mood disorders from breeding events with Neanderthals, he adds.

Why evolution has not wiped out the variants that dispose of psychiatric conditions is not clear, but it may be because the effects are modest and can provide benefits in some contexts, says Libedinsky.

“This kind of work is exciting because it allows researchers to revise long -term questions in human development and test hypotheses in a concrete way using the real world taken from our genomes,” says Simon Fisher at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Yet, this kind of study can only investigate genetic places that still vary between living human-what means it misses older, now universal changes that may have been the key to our development, Fisher adds. Development of tools to investigate “fixed” regions could offer deeper insight into what really makes us people, he says.

Topics: