Happy now?

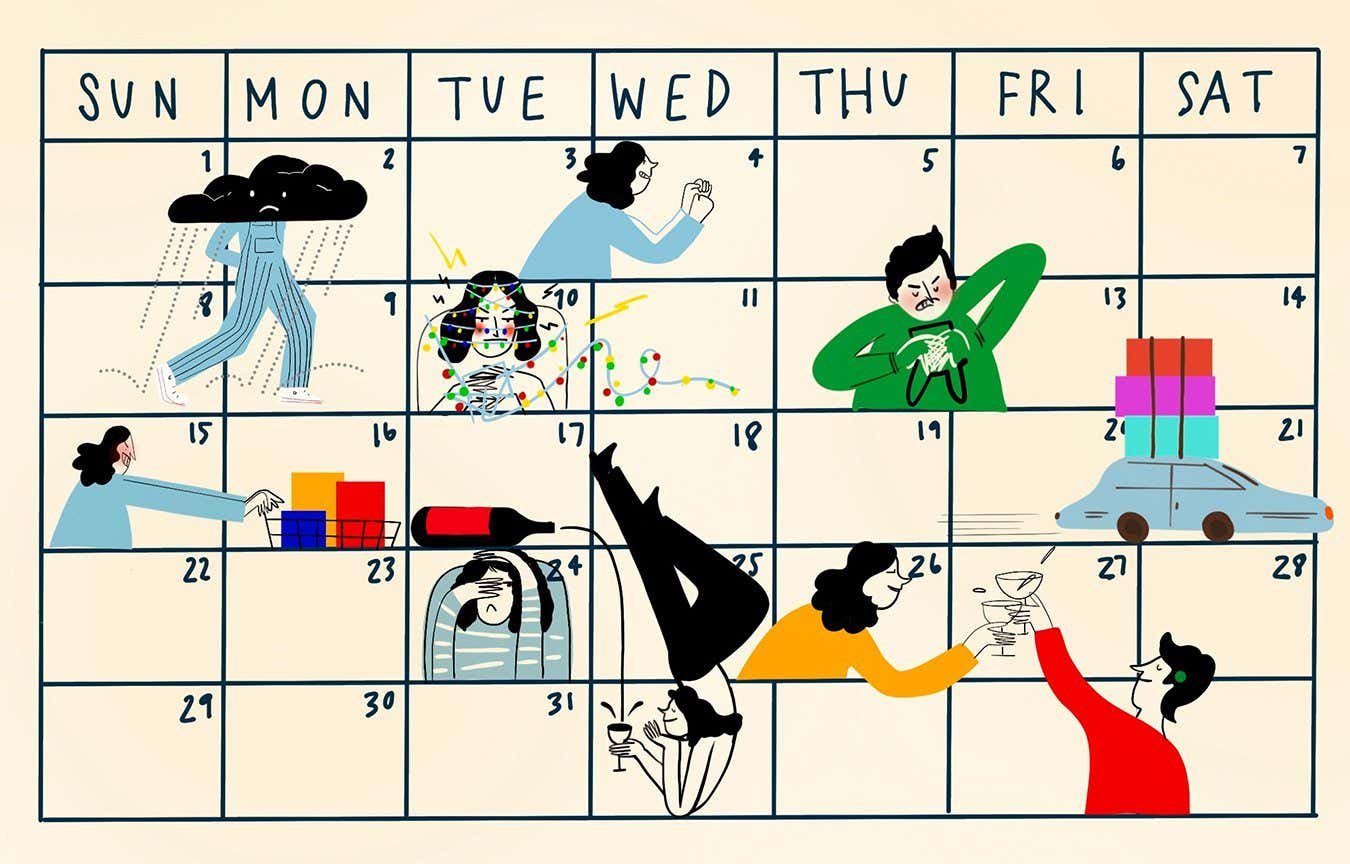

Assuming you’re reading this issue straight away, it’s the post-Christmas hiatus: that weird in-between time between Christmas and New Year’s when nobody’s quite sure what to do with themselves (unless they’re avid shoppers, in which case the January sale has you covered ).

Anyway, Feedback recently learned something new about Christmas. This excerpt came from freelance writer Michael Marshall, who wrote a story about a study on whether children are better behaved at Christmas. If you haven’t read it, the short answer is “no, they don’t”. Parents, feel free to take a moment to grieve that one of your best moves to get the little buggers to behave seems to be doing literally nothing. We would add that the data suggest that some behaviors improved if children were exposed to many Christmas rituals, such as putting up a tree and having fun, and that these rituals could act as a kind of social glue that encouraged children to be friendly and cooperative. Maybe try doing more of that? But we wouldn’t count on a miraculous transformation.

However, that was not the new thing. Michael, we understand, had to leave something out of the story for lack of space. So since we’re in the post-Christmas period, let’s have some leftovers.

The study found that parents became more stressed as Christmas approached. In the run-up, they often worried that it would be a disaster, that key gifts wouldn’t show up, or that Great Uncle Ted would get drunk and say something rude at the dinner table. It got worse during Christmas week, maybe because they were working so hard to prepare that they couldn’t relax and enjoy themselves.

Apparently, it is common for people to only see great rituals as positive experiences once they are over. This is certainly true of weddings, which people look back on as the happiest day of their lives, but if you ask them on the day, they’ll say they’re so nervous they want to throw up. Feedback and Mrs Feedback can both testify that yes, that was what their wedding day was like (Feedback was boosted by a bacon and egg sandwich eaten in the bath and a stiff whisky).

It’s a strange human thing to do something that you absolutely hate in the beginning and while it’s happening, and subsequently declare it the best thing you’ve ever done. Feedback isn’t sure what to make of this, but this morning we noticed Feedback’s felines sleeping soundly in warm spots around the house, and we thought they might be smarter than us.

Fake fake syndrome

Speaking of not being very smart, Feedback is launching a new recurring segment. We call it “generative AIs say the dumbest things”. We suspect that it will be a bottomless well of material, on the level of nominative determinism, and we hereby invite reader submissions to the usual address.

To kick things off, anonymous neuroscience blogger Neuroskeptic recently spotted something strange in the “AI Overview” that now appears at the top of Google Search. For readers unfamiliar with Neuroskeptic, they’ve written about the limits of functional brain imaging—especially when it’s wildly overinterpreted as “revealing people’s thoughts”—and about poor scientific publishing practices.

Neuroskeptics were surprised to see an AI overview describing “kyloren’s syndrome”: “a disease caused by mutations in mitochondrial DNA” that is “often passed from a force-sensitive woman to her children”. This is immediate and obvious nonsense: Kylo Ren is the bad guy Star Wars sequel trilogy, and “force-sensitive” humans only exist in the fictional Star Wars universe.

But it’s actually worse than that. Neuroskeptics coined Kyloren’s syndrome in 2017, as part of a sting to expose predatory scientific journals that do not properly review studies. They wrote a whole fake paper full of Star Wars references, attributed to Lucas McGeorge and Annette Kin, and submitted it to nine journals. Three of them published it—and another accepted it but didn’t publish because Neuroskeptic refused to pay a $360 fee.

Apparently, Google’s generative AI has not fully understood the concept of “context”.

Fast tremors

Feedback is sad to see the end of Taylor Swift’s Eras World Tour. This is partly because we didn’t get to go because we didn’t use our understanding of probability and only registered interest in one concert – which greatly limited our chances of getting to the top. Maybe feedback isn’t as smart as a generative AI.

But the concerts have also been so large that they have produced traceable seismic events. In June, geophysicists at University College London installed nine seismometers near Wembley Stadium in London and recorded the aftershocks. love story produced the largest earthquake, although to be clear it was a magnitude 0.8, so really quite small, followed, appropriately enough, by Shake it off.

Now that Taylor has gone home to (presumably) work on another surprise album, Feedback is looking forward to earthshaking triggered by other tours. We can’t help but suspect that the upcoming Oasis reunion tour might be worth a seismometer or two – if only to detect the exact moment Liam Gallagher loses his temper and stomps off stage, never to return.

Have a story for feedback?

You can send stories to Feedback via email at feedback@newscientist.com. Please enter your home address. This week’s and previous feedback can be seen on our website.