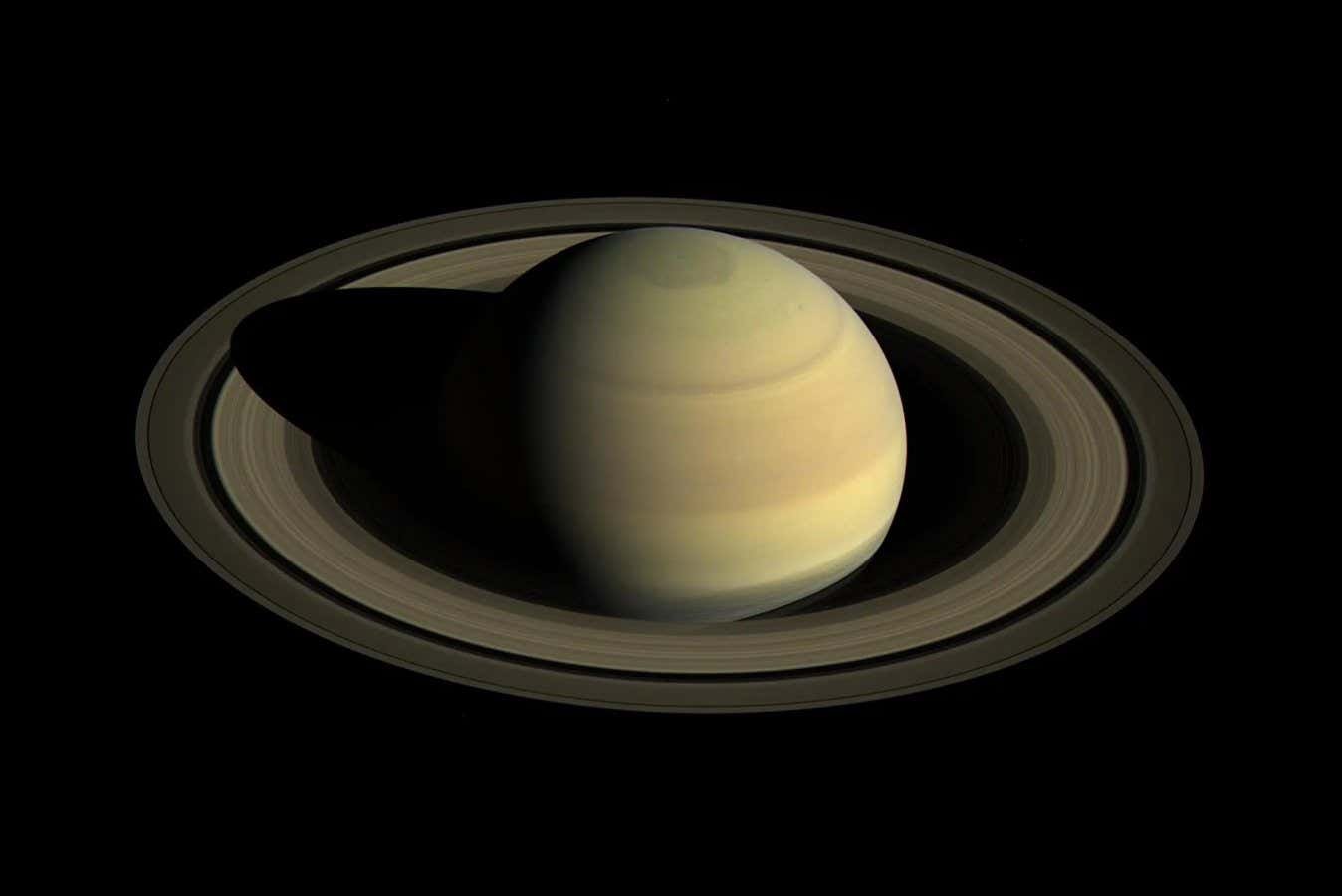

Saturn and its rings as imaged by the Cassini spacecraft in 2016

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Saturn’s rings may be much older than previously thought and may have formed around the same time as the planet, according to a modeling study. But not all astronomers are convinced, and a researcher who was part of a team that calculated Saturn’s rings to be relatively young argues that the new work does not change their findings.

For most of the 20th century, scientists assumed that Saturn’s rings formed with the planet about 4.5 billion years ago. But when NASA’s Cassini spacecraft visited Saturn in 2004, it found that the rings appeared remarkably free of contamination from tiny space rocks, known as cosmic dust. This pristine appearance indicated that they were much younger, with one estimate in 2023 placing them between 100 and 400 million years old.

Now, Ryuki Hyodo of the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science in Japan and his colleagues have calculated that Saturn’s rings should be much more resistant to cosmic dust pollution than previously thought, so that they could maintain a clean appearance for a long time. Hyodo and his team have not calculated a new age for the rings, but suggest they could be as old as the planet, as astronomers used to believe.

Hyodo and his colleagues first simulated how high-velocity cosmic dust, accelerated by Saturn’s gravity, would smash into the rings. They found that the collision would create such extreme temperatures that the impacting dust would have to vaporize. This vapor, after dispersing into a cloud, would then condense into charged nanoparticles, similar to particles observed by Cassini.

The researchers then modeled how these particles would move through Saturn’s magnetic field and found that only a small fraction would settle on the rings, with most being pulled into Saturn’s atmosphere or shot back into space. “The efficiency of accretion of Saturn’s rings is only a few percent, which is much, much less than previously thought,” says Hyodo. This could extend previous estimates of ring ages by hundreds of millions to billions of years, he says.

Sascha Kempf of the University of Colorado Boulder, a member of the team that calculated the earlier, much younger estimate of the age of Saturn’s rings, says he and his colleagues used a more complex method than just the ring contamination efficiency, given how long it takes for material to reach the rings and disappear. The value calculated by Hyodo and his colleagues should not change the overall results for age, says Kempf. “We’re pretty sure this doesn’t really tell us to go back to the drawing board.”

But Hyodo argues that the lower pollution efficiency should change the age dramatically. “They assumed 10 percent efficiency, we reported 1 percent. You can see from the equation that it’s going to be 1000 million years or a billion years.”

Kempf also says that the new simulations assume that Saturn’s rings are made of solid ice particles, whereas the rings are actually made of softer particles of many more sizes than modeled in the study. “If you shoot particles into these rather complex, softer structures, the outcome of such collisions will be very different,” he says.

Hyodo argues that this assumption is standard for many similar studies. “Nobody knows what the effect of different ices is,” says Hyodo. “That may or may not further reduce efficiency.”

Lotfi Ben-Jaffel of the Paris Institute of Astrophysics in France, who was not involved in any of the age estimation efforts, says the new work suggests the rings are not as young as has been claimed in recent years. “It represents a positive step towards the lack of modeling effort required to properly address the fundamental problem of the formation and evolution of a planetary ring system,” he says.

However, Hyodo and his team still need to improve their modeling to better assess the contamination of the rings so they can calculate their age more precisely, he says.

Subjects: