Human metapneumovirus (hMPV) has likely infected humans for centuries

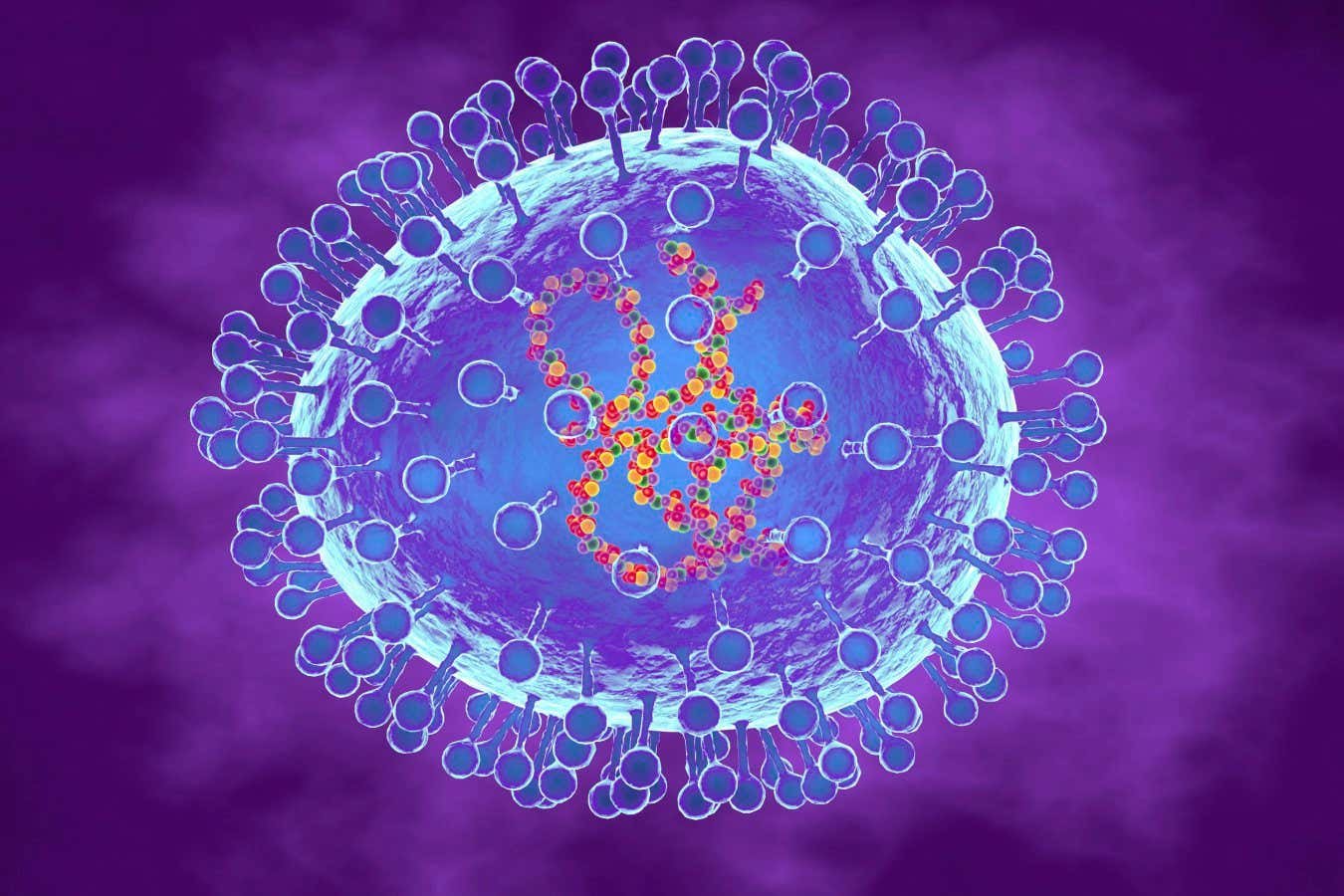

ROGER HARRIS/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Alarmist headlines warning that China is once again being overwhelmed by a mysterious new virus have dominated the past few days. But the virus reported to be responsible for a rise in respiratory infections there, called human metapneumovirus, or hMPV, is actually neither mysterious nor new, and authorities in China have rejected claims that its health system is overwhelmed.

What is human metapneumovirus?

It is one of a variety of viruses known as cold viruses because they infect the cells of our respiratory tract, causing “common cold” symptoms such as a sore throat, runny nose, coughing and sneezing, which can persist for a few days. You’ve almost certainly had an hMPV infection – studies of antibodies show that almost everyone becomes infected by the age of 5. As with the flu, people can be reinfected throughout life as immunity wears off and new variants develop themselves.

How dangerous is hMPV?

In most people it causes only mild symptoms, but like other cold viruses it can sometimes be more serious and even fatal. Serious infections usually occur in people who are vulnerable for any reason, including very young children, elderly people and people with compromised immune systems or conditions such as asthma.

Globally, the virus is estimated to have killed at least 11,000 children under the age of 5 in 2018. By comparison, another cold virus called respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, is estimated to kill 60,000 children globally each year.

How long has hMPV been circulating in humans?

It has probably spread in humans for centuries. The virus was first discovered in 2001 in samples taken from children in the Netherlands who had respiratory infections. Since then, it has been found in stored samples from as early as 1976, while antibodies to the virus have been found in blood samples from the 1950s.

Where did it come from?

Closely related viruses known as avian metapneumovirus circulate in birds, and the human metapneumovirus is thought to have evolved from one of these. However, this is believed to have happened about 200 years ago, so the situation with hMPV is very different from the covid-19 virus, which only jumped to humans in late 2019. While hMPV is now a human virus, it can infect some other animals, including chimpanzees and gorillas.

What kind of virus is it?

It belongs to a group called paramyxoviruses, which consist of a single strand of genetic material in the form of RNA enclosed in a protein coat. Other paramyxoviruses include measles and Nipah. The genome of hMPV is about 13,000 “letters” long and codes for only nine proteins – meaning it has a relatively small, streamlined genome, like many other respiratory viruses.

Is there a treatment or vaccine against hMPV?

There are no specific treatments for hMPV infections or any approved vaccines. But several potential vaccines are under development. For example, in 2024 a team at the University of Oxford began testing an mRNA vaccine designed to protect children against both hMPV and RSV.

Why are there so many cases in China?

It is normal for waves of cold and flu infections to occur during the winter, and some years these waves are larger than others for reasons that are not well understood. More infections mean overall that there will be more serious cases and therefore more hospitalizations. “There is nothing to suggest anything unusual. So far it seems the normal endemic seasonal nasties are doing what they do,” writes Ian Mackay of the University of Queensland in Australia, who points out that there was a similar scare in 2023.

How do we know we’re not seeing the start of another pandemic?

The Covid-19 virus was a new virus, meaning people had no immunity to it. This allowed it to spread widely and made it more likely to cause serious infections. In contrast, the hMPV variant spreading in China differs from other hMPVs by only a few mutations, meaning that most people – apart from young children – already have some immunity.

There have been claims that this new variant is more likely to cause serious infections, but even if that is true, that does not mean it will cause another pandemic. Indeed, Mao Ning, a spokesman for China’s foreign ministry, said on January 3 that the respiratory infections “appear to be less serious and spread on a smaller scale compared to the previous year”.

Subjects: